Director D.W. Griffith often remembered for his controversial film “Birth of a Nation” (1914), embarked on an ambitious project in 1916—”Intolerance.” This epic silent film, with art direction by Walter L. Hall, aimed to depict how hatred and intolerance have clashed with love and charity throughout history. While it may not meet modern Oscar criteria, “Intolerance” remains a scenic triumph that deserves recognition.

The film weaves together four loosely intertwined historical narratives: the Massacre of St. Bartholomew, the Capture of Babylon, the Crucifixion of Jesus, and early 20th-century American justice. Griffith intended to respond to the growing calls for censorship against his previous film, but “Intolerance” went beyond mere storytelling. It marked the beginning of a directorial quest for in-depth visual research to support narratives.

Griffith’s pursuit of realism in set design was evident as he immersed himself in extensive research before production. However, the film’s execution often crossed into exaggerated fiction. While most objects in the film were based on authentic artifacts from anthropological books, cultural motifs were mixed and matched to suit the frame. The Babylonian sequence is a prime example, with elements from various Near Eastern cultures.

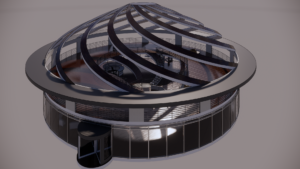

Despite the historical inaccuracy, the film’s sets created a visual world that continues to influence modern films and contemporary architecture. The grandeur of Babylon’s Great Walls, adorned with massive archways, pillar capitals, and centaur statuettes, showcases Griffith’s significant contribution to modern scenic design. The scenes, particularly the storming of the massive set by invaders, were brilliantly captured.

The more contemporary settings in “Intolerance” were equally impressive, from stately ballrooms to the hand-tinted walls of the Louvre palace. However, what truly stood out were the small details that conveyed the characters’ status and authority, such as floral-print wallpaper and quaint sconces.

While the film excelled in creating an “accuracy” of time and place, it occasionally fell short in providing insights into the characters’ struggles. Thus, the final verdict for “Intolerance” on the Scenic Fitch Rating scale is four out of three scenic fitches.

“Intolerance” may not have received an art direction Oscar, but it undeniably left a lasting mark on scenic design, inspiring generations of filmmakers and artists.

Reference:

(1) Merritt, Russell, “On First Looking into Griffith’s Babylon: A Historical Investigation,” in Wide Angle (Athens, Ohio), no.1, 1979.