In Frank Capra’s “Lost Horizon” (1937), a journey from the bustling streets of Baskul, China, to the mythical haven of Shangri-la unfolds. While the film carries a mix of delights and disappointments, the scenic design leaves an indelible mark on the viewer.

Capra and cinematographer Joseph Walker deserve commendation for their visual storytelling prowess. The clarity, lighting, and frame compositions, especially in Shangri-la, offer a visual treat. Multi-camera setups enhance the capture of actor reactions and dramatic sequences, elevating the cinematic experience.

The film’s portrayal of the Douglas DC2, the aircraft for Robert Conway’s expedition, is a visual standout. The plane, rented from American Airlines, is given ample screen time and shines against the mountainous backdrop. Its interior, created on a soundstage, exudes luxury with riveted leather, wood paneling, and glass-ball lamps. The cabin’s spacious feel and dynamic camera work make it a memorable part of the film.

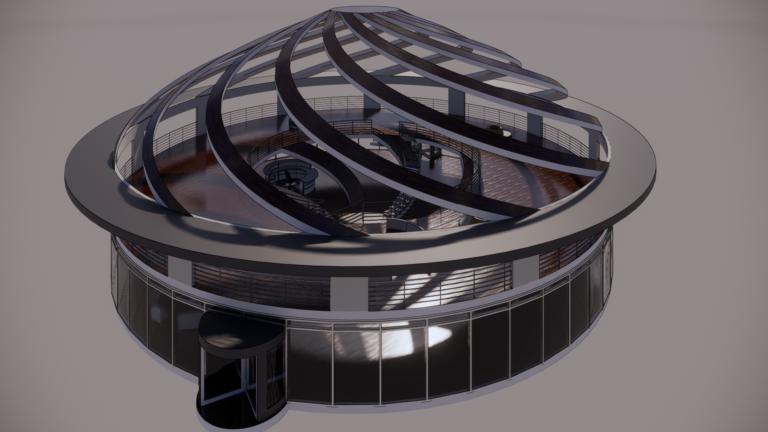

However, as the narrative transitions to the Himalayan utopia, the scenic elements take an unexpected turn. The lamasery lacks the traditional architectural motifs of Tibetan temples, leaving a void in authenticity. While Goosson’s attempt to blend architectural styles and incorporate Asian elements is intriguing, it sometimes feels disjointed.

The film introduces a dream-like aura, but the disparate designs occasionally detract from the overall experience. Star Trek-like doors, tufted interior walls, and leopard-fur wrist cuffs challenge the film’s cohesion.

In spite of these aesthetic challenges, “Lost Horizon” remains a massive production undertaking that largely succeeds. The scenic design, though not without flaws, contributes to the film’s unique atmosphere. In the end, “Lost Horizon” earns a rating of five out of ten scenic fitches, a testament to its ambitious scenic endeavors.