Thought you all might get a kick out of reading a Contemporary Art term paper I wrote for visiting SCAD professor Karl Christoph Kluetsch. I enjoyed the freeing dialog of the class and also found the origin of my feminine imagery fixation.

Originally Published: March 8, 2009

THE STORY

Literature and art have investigated and sometimes dramatized suicide in their commentaries on the human condition. Playwright William Shakespeare traversed the psychological motivations and even romanticized the act of suicide in his epic dramas. One of the most memorable examples surrounds the story of Ophelia. Written in 1601, Shakespeare’s Hamlet was the tragic tale of a Danish prince who tried to avenge his father’s death but ended up destroying everything he cared about. Ophelia was Hamlet’s love interest in the play. Distraught by the death of her father (Polonius), the increasingly erratic behavior of her love (Hamlet), and the absence of her brother (Laertes), Ophelia experienced a psychological break under the strain of events. The noblewoman reverts into crazed ramblings without the men in her life and eventually stumbles off to her death. Ophelia’s last moments are shrouded in mystery because we only hear the poetic announcement of the heroine’s watery demise from Hamlet’s mother, Queen Gertrude. This lack of documented theatrical action in Shakespeare’s play left visual artists a vast playground for interpretation. Long after Ophelia’s last curtain call, artists have revived her tale for new audiences to experience.

HISTORIOGRAPHY

The implications of Ophelia’s story have been rehashed by numerous academics. Some view the character as a pathetic victim, while feminists like Gabrielle Dane profess that “Ophelia’s [suicide] choice might be seen as the only courageous—indeed rational—death in Shakespeare’s bloody drama” (Dane p 423). Dane tried to establish that, by taking her own life, Ophelia made a conscious choice not to live within the regimented confines of cultural roles. There are other studies which may lend validity to this claim. Nona Fienberg points out that Ophelia shows strength when she definitively labels Hamlet’s mental decline and when she insists on a meeting with Hamlet’s mother “to hold a mirror up to the court” (Fienberg p 136). In both instances, her speech patterns were decisive and on par with her male contemporaries. In addition, Leslie Dunn sees Ophelia’s musical ramblings before her death as, “literal and figurative dissonance” and points out that the dismissal of her words in the play speaks to society’s tendency to trivialize feminine identity and actions (Dunn p 59-60). These inclinations to create caricatures or stereotypes extend beyond the pages of the text. When the play is performed, directors take liberties of omission and physical exaggeration to paint Ophelia’s polar extremes. Susan Lamb examined 18th-century theatrical representations of the heroine and concluded that these highly sexualized depictions “in fact erase or obscure the place and influence of women in the public sphere. (Lamb p 106)“ These dichotomous representations have even led to speculative controversy accusing Claudius (Hamlet’s uncle) of impregnating and murdering Ophelia. So, this character as a feminine archetype has become a dynamic and complex path into gender identity. To delineate the impact of Ophelia’s stereotype, I plan to examine the visual expressions of these contradictory themes in contemporary art.

EARLY VISUALS

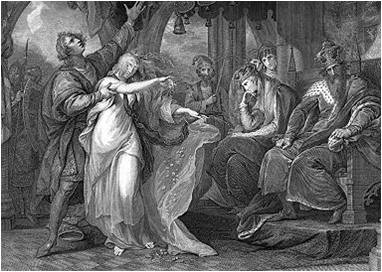

Soon after Hamlet’s performance premiered, images of Ophelia started to appear. Eighteenth-century illustrations, usually associated with the printed manuscript, embraced the British stoic reserve. Ophelia was generally visible sitting or kneeling and devoid of any telling expressions. It was Benjamin West, an American painter of humble beginnings, who brought Ophelia’s emotional struggle to the front stage. West’s painting (fig. 04) showed Ophelia’s mid-wild, abandoned run.

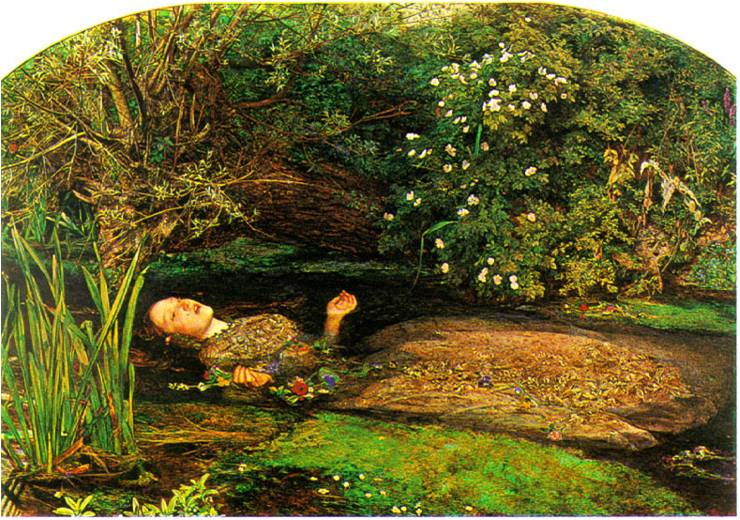

Her head was thrown sideways at an odd angle and her arms flayed out, barely hiding the debris in her tangled hair. Ophelia was shown barefoot and almost pregnant-looking in a gleaming white dress. West’s depiction opens the door for another artist to create what is arguably the most famous image of our heroine. Pre-Raphaelite painter John Everett Millais’s Ophelia (fig. 08) is praised with literally and figuratively plunging into Ophelia’s last moments.

A child prodigy from an affluent English family, Millais’s style was marked by intricate landscapes that seemed to give birth to or seek to encapsulate the floating lady completely. It was the first time that Ophelia was shown horizontally, and her upturned palms captured the hopeless surrender typically associated with her character. Later representations varied but elements used in West’s and Millais’s work are still used to evoke Ophelia’s spirit. In her book, The Myth and Madness of Ophelia, Carol Solomon Kiefer lists some of the visual cliches featuring Ophelia as “young and beautiful,” “frail,” having “consumptive-like pallor” with “long disheveled hair,” “flowing white dress,” “sometimes bare-breasted” and “often depicted at the side of or floating in a stream” (Solomon p 12). These elements string together to solidify a visual stereotype that can be recognized in numerous contemporary scenarios. However, they are ambiguous enough for interpretations to span countless themes and mediums. They weave a complex picture of what Ophelia has come to mean and the ways in which her image has been used in art over the centuries.

THESIS

Ophelia walked the line between childhood innocence and a seductive woman. In the play, she dutifully tried to follow the moral and ethical codes of conduct established by her patriarch. Ophelia was supportive and conspired in the schemes concocted by her sibling. Her beauty fanned the carnal desires of an aspiring warrior, but her will held him at bay, which slipped her into the role of evil temptress. She was most at home in the gardens, surrounded by the creative and controlling force of Mother Nature. Like his contemporaries of the time, Shakespeare scribed this character to embody human frailty and the uniquely feminine divorce from logic and tendency towards witch-like, erratic behavior. However, mystery, intrigue, and even a little courage marked her rebellion against her assigned roles and yearning to explore her own independent, all be it terminal, path. Ophelia epitomizes child, mother, and temptress while managing to die a virginal princess, which catapulted her to the ultimate martyr and strikes a cord for discourse on human mortality. The ability to embrace all these contradictory modalities is one of the reasons Ophelia’s image has survived and is consistently replicated in modern art. To traverse the varying ways her essence has emerged, I have categorized the occurrences into four main groups that (1) speak to woman’s symbiotic relationship with nature, (2) mark the transition into womanhood and the death of innocence, (3) traverse and espouse female sexuality and identity, and (4) explore psychological reflectivity of Ophelia’s character. With that information, I hope to show how Ophelia’s representation in the visual arts relates to the original text and why her character is so often utilized as a creative muse.

WOMEN AND NATURE

Unlike other deaths in Hamlet, Shakespeare sets Ophelia’s passing offstage. Kaara Peterson writes in Framing Ophelia: Representation and the Pictorial Tradition, “[Shakespeare] gives Gertrude this less than typical messenger performance (her only extended monologue in the play) and then provides for its immediate discrediting by the gravediggers. […] There is an epistemological gap in the text that cannot be filled in” (Peterson p 257). Without scriptural evidence, artists have taken symbolic clues from the rest of the play when assembling this scene. Because of the ambiguity, no one depiction can be right or wrong. The outcome is simply a matter of which clues the artist chose to focus on and in what order of importance. John Millais, for example, may have used Ophelia’s last dialog with the court for inspiration. In that scene, Ophelia goes around to the various characters, handing them plants with thematic meaning. In his “Study flowers in Ophelia’s garland to learn folk beliefs,” Shakespeare’s article for the San Francisco Chronicle, Rob Loughran, details how the rosemary Ophelia gave to her brother urged him to “remember” their father’s death and the rue she rationed to Hamlet’s mother and herself, was really calling for “repentance” for their mutual feminine sins. The specificity of such an act leaves us with the impression of Ophelia as the consummate gardener who is knowledgeable and respectful of nature’s powers and meanings. So when Hamlet’s mother describes Ophelia’s death, it is not surprising that it takes place in the garden, surrounded by “crow-flowers, nettles, daisies, and long purple” (Hamlet Act 4, Scene 7, Line 169). Shakespeare’s repeated references to plants in relation to Ophelia reinforce her connection to nature in the script. This motif has been depicted in numerous ways.

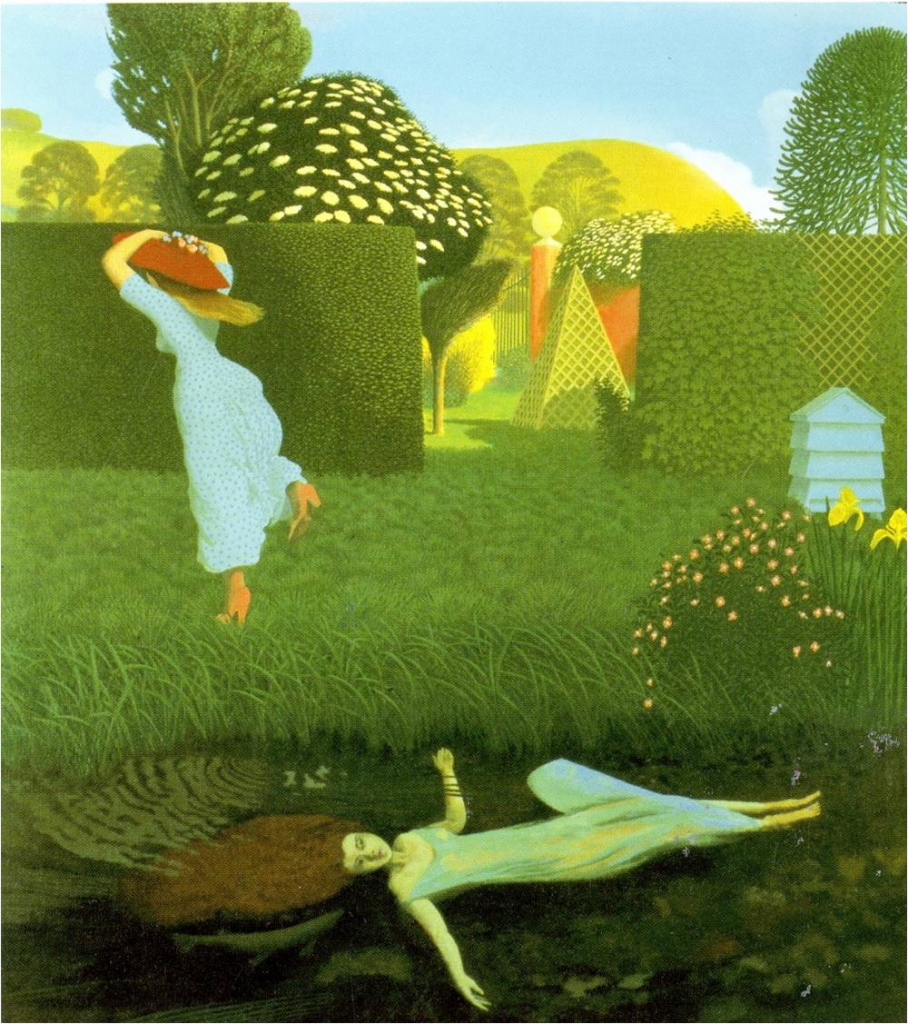

John Everett Millais set the artistic standard for associating Ophelia’s representation with nature, but what was important about his work was how immersed the subject was in its organic medium. Other artists have translated that quality into similar works. David Irnshaw’s The River Bank: Ophelia (fig 02) could be a snapshot of someone discovering the body.

We see very ordered, geometric, organic forms in the top half of the painting, which hints to the story’s domestic garden setting. A woman is shown running back towards the order, clutching tightly to the perfect symbol of decorum, her summer hat. Ophelia lays horizontal below with arms spread, positioned like a fallen crucifix. The monolithic organic masses seem to constrict Ophelia’s form. The lack of three-dimensional contouring and the use of heavily block colors give the “water” a murky quality of soil. So here, Ophelia is buried (locked in a grave) and consumed by nature. She is a part of the landscape and infinitely connected and defined by it.

Although Irnshaw chose to stylize his painting to highlight Ophelia’s oneness with nature, there are also instances of more realistic replications. Charlotte Cotton calls this visual mimicry “reenactments” of popularized fables or myths in her book, The Photograph as Contemporary Art. She cites photographer Tom Hunter as an example of this technique, claiming, “[the] contemporary stimulus for The Way Home was the death of a young woman who had drowned on her way home from a party. The work shows this modern-day Ophelia succumbing to the water and metamorphosing into nature, an allegory that has had a potency for a visual artist for centuries” (Cotton p 55) (fig 01).

Hunter, who was born on the southern coast of England, works to try and find commonalities between the historical pictorial masterpieces and today’s popularized news events. In essence saying that history repeats itself, but in this case linking the occurrence to the girl’s possible drug-induced incapacitation. The young lady occupies less than a quarter of the page, as if at any moment the towering bush will crash down over her or the water will suck her down into the abyss. So like Millais, the proportional footprint of the woman to nature plays a key role.

Iris van Dongen, used a similar distribution in her Ophelia by Night (fig 03).

The matron’s face and body remain primarily in a swelling shadow. Van Dongen, a mixed media artist who works in Berlin but hails from Holland, uses charcoal to literally blur the lines between what is nature and what is human. It is a self-portrait that returns woman, Ophelia in this case, to her roots. So all three artists evoked the sliding scale of proportionality and placement to show their subject’s inherent relationship to nature.

TRANSITION TO WOMANHOOD

Ophelia’s family was determine to stay her quest into adulthood. The men in her life used possessive, object-oriented language towards her and repeatedly referred to her as naive. Before Laertes leaves for France he scolds Ophelia for being “a green girl” if she believes that such a highly ranked nobleman (Hamlet) could actually love her (Hamlet Act 1, Scene 3, Line 101). This talk is followed by numerous others saying that Ophelia was too young to know her own mind. She was seen as an innocent even though she was old enough to inspire Hamlet’s love letters, without any moral repercussions. So she was both woman and child and could be used as inspiration for a transitional exploration.

New York native, Alessandra Sanguinetti, has spent the last decade documenting the lives of two young Argentinean girls as they transition to adults. Sanguinetti works by having her subjects play-act their future fantasies or reenact scenarios based on artifacts brought back from her travels. For her series The Adventures of Guille and Belinda and the Enigmatic Meaning of Their Dreams, Sanguinetti brought back a postcard of Millais’s work and reflected,

“I expected [the girls] to be weary of getting dressed up and lying in cold water for the longish time I usually took to make a picture, but they were instantly attracted to it and wanted to act it out right away. I was glad they were enthusiastic, but at the same time I remember feeling a twinge of sadness and regret at their immediate identification with [Ophelia]” (Wildshut p 8).

The girls may have identified with Ophelia’s image because the idea of floating in water is a freeing experience that isolates you from the rest of the world. It gives you a sense of letting go of personal inhibitions.

Like Hamlet’s character, these young women know that change is upon them and requires time and space for self-contemplation. Water’s transformative connotation is utilized, by Sanguinetti, to denote the next stages in life or the death of innocence. The artist starts this journey with Ophelias (fig 10) but furthers the motif in Times Flies (fig 12), where only the girls’ faces remain above ground.

The book Ophelia: Sehnsucht, Melancholia, and the Desire for Death, reveals Flos Wildshut’s view about,

“[When] they are buried in the soil, with only their heads uncovered, the fantasy depicted becomes more morbid. In their childish dream world, in which a game is just a game, the outside world gradually seeps in. The girls grow more and more aware of their sexuality and the games they play with it are increasingly less innocent, on account of which we as spectator feel more and more like voyeurs.” (Wildshut p 88)

So, as these new Ophelias pursue life post-transformation or beyond their virginal, innocent predecessor, we, as the audience, are the ones left fighting to keep the pure image erect. In the play both Polonius and Laertes warn Ophelia of the dangers associated with a loss of innocence, urging her to protect it as her one useful treasure. To them, innocence and sensuality cannot occupy the same entity, or to gain sensuality is to lose innocence.

Similar uneasy feelings are experienced when viewing Justine Kurland’s comment on New Zealand’s escalating suicide ratio and its transformative aspects in her photograph, Eel Swamp (fig 05). Kurland used children in school attire to, “break from the civilization that their uniforms suggest into a world of wilderness and abandon” and navigate the social topography of girlhood (Wildshut p 7). Much of the photograph peers onto water’s reflective surface so the viewer gets the impression that this carefree time is destined to end while constantly aware of how easily they could become victims like Ophelia.

Even total submersion seems to bring about transformative issues. Desiree Dolron’s worked to physically test this theory in Gaze, Study Number 15 (fig 07).

This Dutch photographer captured a uniquely disturbing scene while submerging her subject underwater. Isolated from outside stimuli for extended periods of time, these people often experienced transformative trances observed in Dolron’s earlier religious-based work, where she followed her subjects to their temples and other sacred locations. As eluded by Charlotte Cotton earlier, it is clear we are privy to something intensely private happening to this young girl. It leads us to question what Ophelia’s last moments entailed and if her “death” really marked a rebirth as a less fragmented woman.

FEMININE SEXUALITY AND IDENTITY

Throughout the play, Ophelia struggles to mold herself to the desires of the men in her environment. When confronted with her family’s disapproval of Hamlet’s professed love, Ophelia’s only reply is, “I don’t know, my lord, what I should think” (Hamlet Act 1 Scene 3, Line 101). What is clear is everyone seems concerned with suppressing Ophelia’s sexuality, culminating with Hamlet’s rejection, “Get thee to a nunn’ry” (Hamlet. Act 3, Scene 1, Line 121). Hamlet, through lenses filled with the deceit perpetrated by his mother, links all sensuality to corruption. So, if you follow her family’s example, Ophelia is not allowed to think for herself and is now told by her love that she should suppress an essential part of her nature. Unfortunately, Ophelia is caught in a pattern of referential dependence. In the end, Ophelia’s identity is so tangled in relationships that their absence has disastrous results. Some modern artists chose to expose this repressed sensuality and, in conjunction, recapture the power of her feminine identity.

As an eccentric surrealist painter, Leonor Fini has a unique perspective on the fluidity of the feminine essence. All throughout her tumultuous childhood and transient adult life, she has literally assumed both male and female roles. This started under threats of kidnapping from her father, where Fini’s mother dressed her up as a little boy. Suppressing and switching between genders became a way of life. Consequently, Fini’s Ophelia (fig 09), blazes like the phoenixes featured in her other works.

The heroine dominates the canvas and boils the surrounding water as she spreads her sexuality. In The Art of Suicide, Ron M. Brown highlights the contrasting nature of Fini’s version. Although the key compositional elements are present, Brown sees this protagonist “as a muddled figure with a tortured expression on her face that flies in the face of the dream-like quality invested in [other] Ophelia imagery…[this] is a dirty death, and the dirt might symbolize her own entrapment in the plot” (Brown p 206). I tend to disagree with Brown’s assessment of the meaning behind Fini’s painting. The figure’s chin is proudly inclined and her arms are extended in a dancer-like pose. Her palms are down, not open skyward in a pleading gesture. This is not a damsel in distress but a powerful woman who seems to be rising again, as Ophelia: sensuality personified.

Interesting comparisons can be drawn between Fini and the new mixed media work of Amie Dicke. The title, Whirlwind of tempestuous fire (fig 06), should indicate Dicke’s focus. This work features intertwining vines of color and form, which once were an editorial layout for a fashion magazine. Dicke uses these found images to meticulously extract sections, creating a web mosaic which she then overlays with layers of ink. Like FIni’s Ophelia, this character extends her tendrils over the piece with her hair fanned out around her. Art critic Ana Finel Honigma said this about the work as a preface to her 2007 interview with Dicke:

“Some critics have offered superficial connections between Dicke’s practice with her knife and cosmetic medical procedures, but the unmistakable morbidity of Dicke’s gothic glamour girls is not, as they mistakenly argue, a feminist criticism of fashion. Instead, her skinless sirens serve as proof that ‘eroticism is assenting to life, even up to the point of death,’ as stated by Georges Bataille. Dicke’s succubae remain confident and enchanting because they have been distilled down to their most essential erotic elements. Even without their skin, the girls beckon.”

In that same interview, Dicke talks about selecting images that have a decadent quality and dignified postures like upturned noses. Her women have lost their surface and hold on to life through Dicke’s pursuit of meaning behind their sensuality. Transforming those images of beauty into artifacts of decay forms direct links to Ophelia’s suspension in water. Dicke is trying to explore whether the fundamental essence of feminine sexuality is housed on the surface or emanates from the core spirit.

Other artists try to explore whether skin itself evokes the same quality of existence. Ironically, it was her own father’s tragic drowning that spurred Paola Ebanista’s fascination with skin. The Spanish artist uses large blocks of pigskin, which are either sown or woven together. In her photographs, Women (fig 14) and Ophelia in the Rain (fig 13), Ebanista constructs feminine figures and suspense them in formaldehyde. In her book Skin, author Heide Hatry explains the duality that exists once the skin is viewed separately from the body:

“Ebanista’s deformed, faceless drowned corpses (Ofelias) are symbols of bodies, ciphers of thee transitoriness of life, oscillating between abstraction and objectivity. Pale white, they stand in stark contrast to their environment; one moment they feel like foreign bodies, yet the next they seem completely absorbed into nature… It’s disturbing, shocking image that literally gets under one’s skin — because it confronts us with death in such and unusual way. (p 43)”

By “unusual,” Harty refers to the floating deaths featuring pale but beautiful Ophelias. In addition to these mock bodies, Ebanista also develops wearable second skins, which intensify the fetishistic nature of her work. Once the initial aversion subsides, questions about mortality and skin’s relationship to identity arise.

This shed skin is an example of Abject art. According to Rosalind Krass in Informe without Conclusion, the emergence of “abjection” as an expressive mode was an insurgence rejection of previous artistic movements (Leung p395). It is an exploration of the tipping point between being held (suffocated) by precedence and expelling everything. Krass describes this losing battle for autonomy as, “the body’s own frontier, with freedom coming only delusively as the convulsive, retching evacuation of one’s own insides, and thus abjection of oneself” (Leung p 397). This graphic depiction can be taken literally and/or figuratively to indicate a fascination with the mid-range viscosity of slimy (oozing) bodily fluids or the shell that remains. The skin, our vessel, could be seen as the “leech-like past that will not release its grip…[and contains] its own form of possessiveness,” which the movement tries to explore, says Krass (Leung p 397). The possessiveness mentioned seems to take on a feminine quality even in Ebanista’s work. The idea of using the waste of people and things to create a symbolic link between the high [beauty] and lows [nothings] of life is a pervasive idea that runs rampant through abject theology. So, Ebanista’s work also serves to dissect the meaning of sensuality for which Ophelia is praised. The character is young and beautiful when she is taken by water, but Ebanista’s Ophelia shows that even in death, we would be drawn to her and possibly suffer from the guilt of perversion afterward. For Hamlet, Ophelia was “an object” to which he was both profoundly attracted and expressly repulsed. So, even in written form, this woman epitomized abjection.

PSYCHOLOGICAL MIRROR

Shakespeare was known for creating reflective parallels in his work. Laertes’ loving relationship with his father allows you to question Hamlet’s loyalty to his patriarchal ghost and consequently understand Laertes’ immediacy for avenging action vs Hamlet’s hesitation throughout the play. Hamlet and Ophelia both suffer through psychological hardship but Hamlet works through his feelings in writing while Ophelia turns to songs that cannot be understood by her peers. Hamlet accuses the women in the play of “frailty” or haphazardly switching loyalties once their sexuality has been released. The Queen could be seen as guilty of this crime, but Ophelia’s loyalty only shifts because of Hamlet’s own actions. And finally, it is upon Ophelia’s death, literally at her gravesite, that Hamlet sees his indecisiveness for what it is and declares, “I loved Ophelia” (Hamlet Act 5, Scene 1, Line 269). Similarly, there are perceptible threads of psychological discourse in visual representations of Ophelia. When the work employs “actors” to tell the story, it seems to shift the focus away from the viewer inward to the emotional motivations of the characters depicted and the individuals who played the roles.

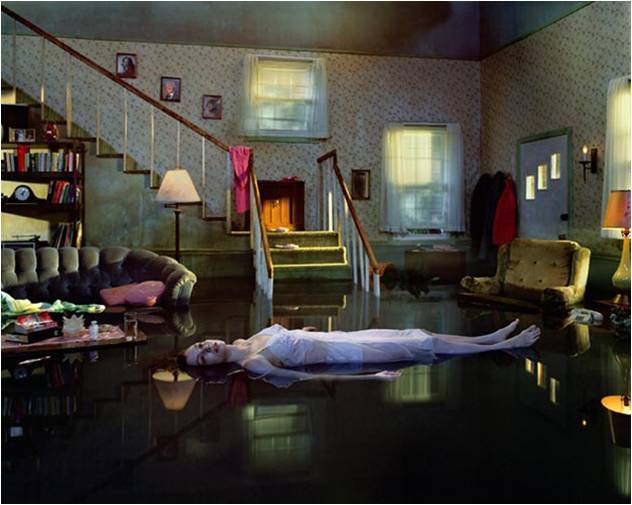

When we first encounter Gregory Crewdson’s Untitled (Ophelia) (fig 11), we stare into a downstairs living room with physical evidence of post-war suburban life scattered all around.

From the cascading family photos lining the stairwell and fuzzy, pink bed-slippers discarded mid-step, the winter jackets waiting on the coat rack by the door, or the well-read books and unfinished glass of water on the coffee table, all point back to a thriving family unit. These items lay undisturbed, as if the pool of water, below this threshold, crept in unsuspectingly. The inky black liquid threatens to slowly overtake the whole scene, carrying its first victim, a beautiful female corpse. Her eyes are open and facial expression is relaxed, contemplative, and even mildly angelic. The skirting light of daybreak washes over our victim, surrounding her in a halo of reflections on the water’s opaque, still surface. The fact that we can’t see what is below the surface is both figuratively and literally frustrating for the viewer. This woman died in a vulnerable, undressed state and the viewer is plagued with curiosity for the story behind, or underneath, the image. By transposing Ophelia’s tale inside a suburban structure, we are left without a natural disaster or accident to blame. This narrative was deliberate, so alone we must look inside the mind for the answer. During an interview with a literary scholar, Bradford Morrow, Crewdson explained that he was always interested in the “ambiguous narrative” that helped his audience question the psychological struggles behind his character’s strange actions (Crewdson p 17). So he is reenacting the popular fiction to examine his own fascination concerning what drives people, or in this case what would make a suburban Ophelia take her own life.

Crewdson’s fascination with psychological drivers started young when he would try to listen to his father’s therapy sessions with psychiatric patients through the floorboards of his house and then develop his own explanations for why they needed his father’s “help.” It was out of this curiosity that Crewdson’s work was forged. It seems ironic that the elaborate productions and surreal environments he creates are really an attempt to isolate or identify himself. Charlotte Cotton, from The Photography as Contemporary Art, classifies his narrative work as “tableau-vivant”: “[Crewdson] worked with a cast and crew of the kind found on a film set…it is not only the display of rituals and the paranormal but also the construction of archetypal characters that carry out these acts that create the psychological drama” (Cotton p 28).

The term tableau vivant translates from French as “living picture” and grew out of practices where whole theatrical sets were constructed and appropriately lit, only to have the actors “play” statues. Crewdson uses this technique to create surreal and vague moments in time. After the photo is taken, some minor digital manipulation is used to clean up the shot but the majority of Crewdson’s creative efforts occur before the aperture shuts. The result is a still life, which, from every angle, asks the viewer to identify what is wrong with this “perfect” picture of Ophelia’s contemporary life.

A similar ambiguous intent is used by Japanese photographer Izima Kaoru. Kaoru collaborates with models to construct their “perfect death,” complete with the appropriate designer attire. Flos Wildschut, in Ophelia: Sehnsucht, Melancholia, and Desire for Death, praises Kaoru’s work, saying, “the outright aesthetic quality ensures we [the viewer] keep death at bay. Its overwhelming beauty does not allow for comparison with our own death, which is why we can bear to stand the images and even admire them. (Wildschut p96)” Each model receives several frames, starting with an aerial shot (obscuring the model to a distant figure) and successively becoming more detailed until we stare right into the glassy eyes of the deceased. In Igawa Haruka, wearing Dolce Gabbana (fig 15), we see a railway bridge over calm waters, then shift to a horizon view down in the foliage looking over the rim of the embankment.

Next follows a groundhog perspective down the road from Haruka. The last two photos show the blood oozing from under her collar bone. The red color is in stark contrast with her pale skin and even more significant is the color control exhibited between the landscape and the subject. All pointing to the fact that Haruka’s injuries were not self-inflicted, this was not a suicide. That is until you consider that the models themselves have constructed these scenarios. They are willing participants in this project, instantly drawn, like Guille and Belinda, to the idea of acting out their own death. Although these tales do disparage the fashion industry, there is a bigger psychological impact on facing your mortality as adults. Being in that moment, having volunteered to die, these models embody everything Ophelia stands for, beauty, frailty, and a slight mental imbalance. Each death is specific to the model so, as actresses in a story of their making, they are forced to contemplate their motivations for selecting this particular demise.

CONCLUSION

The story behind Ophelia remains a strong presence in contemporary art partially because the source text gives no definitive direction. This allowed an artist to utilize the entire play as a basis for their depictions. In Hamlet, Shakespeare constructed characters that composited multiple prevalent ideals which we, as the audience, are still trying to decipher today. For Ophelia, he layered contradicting models of innocence and sensuality, frailty and strength and a divide yet oneness with nature, to name a few. Her character traversed so many emotional states in the play that artist are both pulled and repelled by the implications surrounding her death. She is both an object and a person, from which psychological themes can be imprinted and/or extracted. This objectification idealized and trivialized her death into its current themes of aesthetic beauty. The canon of work that is Ophelia contains enough complexity to allow an artist to express their own cultural or emotional biases without corrupting the original essence expressed by Shakespeare. She motivates uninhibited explorations into mortality because her demise was unjust and universally pitied. Ophelia passes on the verge of adulthood and “out of her mind”, so she was a literal and figurative shell of herself. Into this abject vessel, artists are allowed to pore their own focused impressions, so Ophelia is the quintessential vacant muse.

WORKS CITED

- Crewdson, Gregory. Dream of Life. Salamanca, Spain: Ediciones Universidad de Salamanca Ediciones, 1998.

- Cotton, Charlotte. The Photograph as Contemporary Art. London: Thames & Hudson, 2004.

- Krass, Rosalind. “Informe without Conclusion”, in Theory in Contemporary Art since 1985. Edited by Zoya Kocur and Simon Leung, 2004. p. 395-407.

- Brown, Ron. The Art of Suicide. London: Reaktion Brooks, 2001.

- Finel Honigman, Ana. “Amie Dicke Talks to Ana Finel Honigman”. Saatchi Galery Online. February 21, 2007. http://www.saatchi-gallery.co.uk/blogon/art_news/amie_dicke_talks_to_ana_finel_honigman/1567

- Hatry, Heide, ed. Skin. 2006: Amalgamated Book Services.

- Ophelia: Sehnsucht, Melanchola, Desire for Death. Amsterdam: Uitgeverij De Buitenkant, 2009

- Solomon Kiefefer, Carol, ed. The myth and madness of Ophelia. 2001: Amherst, Mass. : Mead Art Museum, Amherst College.

- Dane, Gabrielle. “Reading Ophelia’s Madness.” Exemplaria 10 (1998): 405-423.

- Dunn, Leslie C. “Ophelia’s Song’s in Hamlet: Music, Madness, and the Feminine.” Embodied Voices: Representing Female Vocality in Western Culture. Ed. Leslie C. Dunn and Nancy A. Jones. New Perspectives in Music History and Criticism. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1994. 50-64.

- Fienberg, Nona. “Jephthah’s Daughter: The Parts Ophelia Plays.” Old Testament Women in Western Literature. Ed. Raymond-Jean Frontain and Jan Wojcit. Conway: UCA, 1991. 128-143.

- Lamb, Susan. “Applauding Shakespeare’s Ophelia in the Eighteenth Century: Sexual Desire, Politics, and the Good Woman.” Women as Sites of Culture: Women’s Roles in Cultural Formation From the Renaissance to the Twentieth Century. Ed. Susan Shifrin. Aldershot, Eng.: Ashgate, 2002. 105-123.

- Loughran, Rob. “Study flowers in Ophelia’s garland to learn folk beliefs, Shakespeare.” San Francisco Chronicle. December 23, 2006. http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?f=/c/a/2006/12/23/HOGVNN39851.DTL